A vibrant, cosmopolitan and competitive research community

by Alun Evans

- Date

- 13 Jun 2017

Published in British Academy Review, No. 30 (Summer 2017).

The print version of this article can be downloaded as a PDF file.

Alun Evans has been Chief Executive of the British Academy since July 2015.

Writing this in the midst of the 2017 General Election campaign I am reminded of Harold Wilson’s famous maxim that ‘a week is a long time in politics’. If a week is a long time, then looking back over a year serves to remind us what a transformation has taken place internationally and domestically in our political landscape over that period. This time last year, Prime Minister May, President Trump and President Macron were all in the future. The Brexit referendum had not yet taken place. So now is perhaps also a good time to reflect on what the British Academy has achieved over this tumultuous period of change.

The changing landscape in higher education

The past year has been a time of unprecedented change in the higher education landscape, offering numerous opportunities for the British Academy to promote the value of the humanities and social sciences.

We worked closely with our sister national academies – the Royal Society, Royal Academy of Engineering and the Academy of Medical Sciences – as well as through parliamentarians, particularly in the House of Lords, to propose changes to the Higher Education and Research Bill as it passed through Parliament. The Bill received Royal Assent in the pre-Election ‘wash-up’ and will lead to the most significant changes to the education landscape in 25 years. It enables the creation of UK Research and Innovation, uniting the seven existing disciplinary research councils into a single strategic body. UKRI presents many opportunities to improve the way in which research funding is administered in the UK, and the British Academy will continue to press to ensure that the voice of humanities and social sciences is heard loud and clear in the new organisation.

The creation of UKRI presents particular potential for the support and funding of interdisciplinary research. Most of the major challenges which society faces – climate change, growing inequalities, computerisation of occupations – require interdisciplinary research and co-operation. The British Academy published a major policy report on this topic in July 2016. Crossing Paths looks at the opportunities and barriers at different career stages and institutional levels, and recommends changes to the way research is evaluated and to funding structures which would overcome the currently perceived risks of undertaking interdisciplinary research.

We also consulted widely with our Fellows, award holders, and subject communities through the learned societies network to respond to the UK higher education funding councils’ technical consultation on the second Research Excellence Framework due to take place in 2021. We welcomed the way in which the proposals sought to deliver the principles set out in Lord Stern’s independent review and to reduce burden and gameplaying, but suggested that some of the new components could introduce unintended and potentially negative consequences and should therefore be properly piloted and reviewed before they are introduced.

Outstanding individuals, innovative research

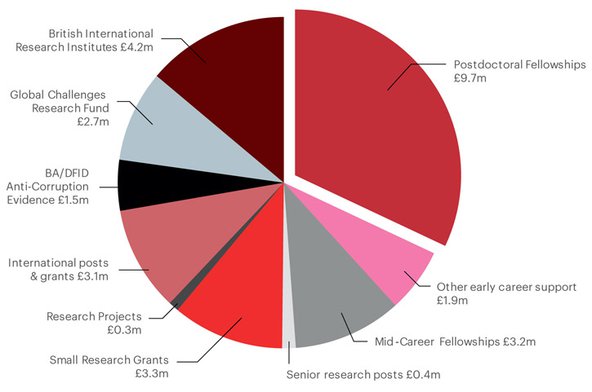

One of the most important roles of the British Academy is the provision of funding opportunities for outstanding individuals and innovative research across the humanities and social sciences. The range of Academy schemes for supporting research is shown in Figure 1, along with an indication of the sums that we disbursed in the past financial year.

Figure 1: British Academy expenditure on research posts and research grants in financial year 2016–17

The scheme that supports the largest number of research endeavours is the Small Research Grants programme. This popular scheme is resourced from public funding and a wide range of additional sources, principally the Leverhulme Trust, but also the Society for the Advancement of Management Studies, the Modern Humanities Research Association and others. Almost 400 awards were made in 2016-17, spread among applicants at 84 different institutions (and 16 independent scholars).

Another important strand of funding provides senior academics with a period of leave to undertake or complete a major piece of research, freed from the day-to-day stresses of teaching and administrative duties. In May 2017, the latest recipients of British Academy/Wolfson Research Professorships were announced. The standard and calibre of applications were of the highest order and our awards committee were faced with some tough choices when they were whittling the shortlist down to the final four. The value of both these Research Professorships and the British Academy/Leverhulme Senior Research Fellowships is illustrated in the two articles later in this issue, by Professor Peter Wade and Dr Mark Harris.

But the jewel in the crown of our funding schemes – the British Academy Postdoctoral Fellowships – continues to play a crucial role in bringing on the next generation of outstanding academics. It has been a particular pleasure in this past year to mark the 30th anniversary of the first of these early career fellowships to be held, with a celebratory reception held at the Academy in April 2017. The impact of the scheme in transforming the lives of individuals is well demonstrated in an article later in this issue.

Global Challenges Research Fund

The year has also seen the evolution of British Academy research funding programmes made possible by the government’s Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF).

The GCRF is a £1.5 billion fund (running from 2016 to 2021) which aims to support cutting-edge UK research that addresses the challenges faced by developing countries. The GCRF, which forms part of the UK’s Official Development Assistance (ODA) commitment, is managed by the Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), and is being delivered through a number of partners. As one of these partners, the British Academy is providing research funding through some specific schemes that we are developing.

In December 2016, the British Academy announced that we would be funding 16 major research projects through the first GCRF scheme it has developed – the Sustainable Development Programme. Professor Paul Jackson (University of Birmingham), appointed as Programme Leader, has explained the raison d’être of the scheme. ‘The UK Government aims to eradicate extreme poverty by 2030, and the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals offer a tremendous framework for making the world a better place for millions of people. However, we currently have only a partial understanding of what works and what doesn’t, and the UK needs an approach that is based on evidence to evaluate the effectiveness and value for money of international aid efforts. Focusing on the core areas of governance, growth and human development, the British Academy’s Sustainable Development Programme is an excellent opportunity to develop research that is not only academically excellent, but also has real impact on people’s lives.’

We are currently assessing grant applications received for our second GCRF scheme – the Cities & Infrastructure Programme. The Programme seeks to enable UK-based researchers to lead interdisciplinary, problem-focused research projects that address the challenge of creating and maintaining sustainable and resilient cities. Projects should produce the evidence needed to inform policies and interventions for improving people’s lives in fragile or conflict-affected states or in developing countries.

And in May 2017, the British Academy announced the launch of its third GCRF scheme – the Early Childhood Development programme; this scheme is run in partnership with the Department for International Development.

Extending our resources

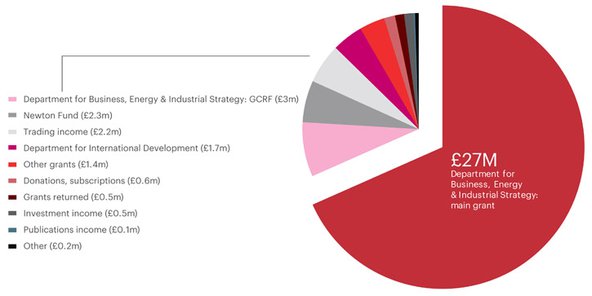

For the British Academy to be able to sustain and extend the research opportunities that it provides, it is crucial that we continue to explore new funding streams. Figure 2 shows the sources of Academy income in the financial year 2016-17. An important element is the revenue generated for the Academy by its wholly owned subsidiary, Clio Enterprises Ltd, through hiring out the many excellent meeting spaces within our home at 10-11 Carlton House Terrace.

Figure 2: British Academy income in financial year 2016–17

During 2016-17 the British Academy received over £1.9 million in philanthropic support from private funders including trusts and foundations, learned societies, individuals and companies – some of whom I have already mentioned. We are enormously grateful to these supporters who enable the Academy to undertake events, award prizes, carry out policy work, and support a dazzling array of research in our disciplines. This important support strengthens the Academy’s independence from government, and enables us to act and respond quickly to external pressures and pursue strategically important initiatives.

In 2016 the British Academy began work on a new research and engagement programme that is being made possible through private funding sources, on the ‘Future of the Corporation’. This programme seeks to explore the nature of business and its role in society and to drive positive change in the world through enabling and encouraging businesses to embed socially and environmentally responsible purposes at their core. The Academy has developed a Steering Group and Corporate Advisory Group to guide the project and ensure it remains relevant to business, and is working closely with government and other organisations active in the field. The ‘Future of the Corporation’ is discussed in much more detail in the interview given to the British Academy Review elsewhere in this issue by the project’s academic lead, Professor Colin Mayer FBA. And we are already developing plans for our second major programme on the ‘Future of Democracy’.

Diversity

On becoming Chief Executive, one of the things I said that I wanted to stress was that the British Academy should be seen to be more representative of the community we seek to serve. And whilst we will always seek to elect Fellows and fund research on the key criterion of excellence, it is also essential that we ensure all of the community have the opportunities to be part of our work. During the past year a working group chaired by one of our Fellows, Professor Sarah Birch, looked at what more the Academy might do to promote greater diversity. We already have a good track record. For example, looking at all our grants awarded, some 54 per cent go to women, and some 15 per cent go to members of the Black and minority ethnic community, compared to shares in the population of 53 per cent and 12 per cent, respectively [the percentage figures are for grants awarded in 2015-16]. But the working group also came up with some very sensible proposals on promoting greater diversity in our Fellowship, including in terms of recruiting our Fellows from as broad a range of institutions as possible, and ensuring that emerging and minority disciplines are represented. I shall continue to follow how well we perform across all these diversity dimensions over the coming year.

By word of mouth

In the interview that I gave to the British Academy Review when I took up post two years ago, I said ‘I think we have a fantastic story to tell. Perhaps we have not told it quite as loudly and vigorously as we could have done in the past. That is one of the things I want to do.’

I have had great personal pleasure in leading a series of British Academy ‘roadshows’ to UK higher education institutions to explain what we do and the opportunities for funding young researchers in the humanities and social science. I have been to Belfast, Bristol, Manchester, Sheffield and Durham, and will keep travelling this year to take our message out widely. Wherever we go the Academy is welcomed and there is real enthusiasm for what we are seeking to achieve. But we can never take for granted the assumption that academics working in the humanities and social sciences are fully aware of all the ways in which the Academy can support their endeavours.

As an Academy we also have a duty to engage more widely with non-academic audiences. And so this past year we have had another very full programme of events aimed at a wider public audience at our Carlton House Terrace premises, and we have also sought to take our public events ‘on the road’. The series of British Academy Debates on ‘Inequalities’ (autumn 2016) and on ‘Robotics’ (spring 2017) included events in Bristol, Leicester, Edinburgh, Belfast, and even one in Brussels. And in the last 12 months we have reached large audiences through our partnership events at the Edinburgh International Book Festival, the Cambridge Literary Festival, the Oxford Literary Festival, and the Hay Festival.

June 2016 saw the initiation of our first British Academy Soirée, as a showcase for the work of the British Academy. The best exemplars of humanities and social sciences scholarship are our own Fellows of the British Academy, and a particularly effective feature of the Soirée was a series of short ‘pop-up’ talks by Fellows of the British Academy about their work and interests. We have since extended this idea by starting a regular podcast From Our Fellows, in which Fellows offer brief reflections on what is currently interesting them. The range and depth in subject matter, perspective and tone have quickly established this as essential listening for anyone wanting to understand what academics working in our disciplines really do.

Where we live now

In the previous article in this issue, Lord Stern drew attention to the continuing lack of confidence that people have in institutions and in politics. A key consideration in understanding people’s concerns is to appreciate what their place means to them.

In March 2017, the British Academy announced the findings of Where We Live Now, a major project seeking to understand how people feel about the places in which they live, and what this means for creating policies that will improve people’s lives.

As part of this landmark project, the British Academy examined what makes a place special; how where we live impacts our health and well-being; and how we can use local knowledge to increase local productivity. At a time when many decisions are being devolved to cities and regions, the British Academy aimed to understand these questions and how they relate to people’s attachment to places – be it a street, village, town, city, county or country.

Where We Live Now took the British Academy around England and Wales to gather opinions on how we can use the way people feel about the places where they live and work, to create and manage new policies. We have discussed a number of aspects of, and barriers to, place-based productivity strategies in England and Wales: place quality, health, housing, employment, skills, infrastructure, planning, post-industrial decline, culture and the environment. As a result we have produced four key briefing papers, a collection of perspectives including eight essays, four case studies and a variety of poetry and imagery, and two policy papers.

And looking ahead, in the coming year we will be bringing to conclusion another major piece of research work which the Academy has been leading on ‘Governing England’. The Governing England project brings together place-based perspectives with questions of governance, representation and the constitution. Ahead of the Metro Mayor elections in May 2017, we held events across the country to explore devolution in England. A report on the conclusions to be drawn from these roundtables will be launched at a conference on ‘Governing England: Devolution and Identity in England’ on 5 July 2017. Through Governing England, the British Academy seeks to provide valuable insights into what these and other changes mean for our local democracy in a changing world.

Brexit

But the most significant constitutional change of the past 12 months has, of course, been the aftermath of the European Union Referendum in June 2016 and the vote to Leave the EU. As we wrestle individually and collectively to understand the implications of this profound geopolitical shift, the British Academy is seeking to provide balance, insights and perspectives to help us find our way – all based on the best evidence and expertise available.

The British Academy publication – European Union and Disunion: Reflections on European Identity – aims to illustrate the feelings, attitudes and sentiments we hold towards Europe today and have done in the past, and to demonstrate how these can be and have been used, mobilised and at times distorted in politics and public discourse. Critically, however, the contributions in the publication also re-imagine these narratives of Europe – both positive and negative – and aim to look forward to a new looking glass of how both nation and Europe can be harnessed to the same societal project. [Note: European Union and Disunion: Reflections on European Identity, edited by Ash Amin and Philip Lewis (British Academy, May 2017), arises from a November 2016 British Academy conference on ‘European Union and Disunion: What has held Europeans together and what is dividing them?’ That initiative has been adopted by All European Academies (ALLEA) as a programme of activities, including further conferences and publications.]

And in June 2017 the British Academy has hosted a conference to examine the idea – propounded as part of the Brexit-inspired narrative of a ‘truly Global Britain – of reaffirming and strengthening ties with ‘old friends’ across the English-speaking world – the so-called ‘Anglosphere’ – particularly Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States [see BA Blog piece by Andrew Mycock].

Brexit will continue to be a major focus of our attention in the coming year. The humanities and social sciences are the essential disciplines for shedding light on the complex issues – legal, political, economic, cultural – surrounding the UK’s disengagement from the European Union. As one example of our engagement in this area, the British Academy has been working very closely with the Royal Irish Academy on the set of issues that the island of Ireland now faces and how the border will operate when the UK leaves the union.

But Brexit also brings with it concerns for the future health of research in our disciplines. On this matter, we have provided written evidence in recent months to three parliamentary select committees, as well as oral evidence by our President; and we have convened two joint statements from the seven national academies in these islands [the British Academy, the Royal Society, the Royal Academy of Engineering, the Academy of Medical Sciences, the Royal Society of Edinburgh, the Royal Irish Academy, the Learned Society of Wales]. In these submissions, we have stressed the importance for the future of UK-based research of addressing the mutually entwined issues relating to resources, people, collaboration and regulation. We have, for example, called for all non-UK EU academics and their dependants currently in the UK (or accepting employment here before the time the UK leaves the EU) to be provided with permanent residency. We have also highlighted how successful UK-based humanities and social sciences researchers have been in EU competitive funding programmes – in particular grants awarded by the European Research Council, a world-leading frontier research programme, which simply cannot be replicated here in the UK alone.

Delivering global leadership in research is a strategic priority of the British Academy. We will continue to stress the value to UK research of international collaboration and mobility – beyond just the European dimension. We will continue to make the case for a vibrant, cosmopolitan and competitive UK research environment.

*

Finally, and on a personal note, I should like to thank Nick Stern for the leadership he has provided to the Academy over these past four years as President. He has played a leading role in raising the profile of the British Academy, and emphasising at all times the centrality of the humanities and the social sciences to all of the key challenges of our time which we as a nation are facing. I shall miss his friendship and wise counsel. I am equally looking forward to welcoming and working with his successor Professor Sir David Cannadine.