Unexpected facts that shake up the popular imagery on Prehistoric hunter-gatherers

by Dr Emmanuelle Honoré

6 Apr 2016

If I tell you ‘Close your eyes and imagine… the hunter-gatherers of prehistoric times’, what comes to your mind? I would bet my trowel that you are thinking to stocky, sturdy and long-haired men half-dressed in animal skins, hunting together or knapping stone around a camp fire near the entrance of a cave.

Don’t blame yourself for having such a caricatured vision! No one fuels this myth more than we, as archaeologists, do. If you take a glimpse at the publication record in the field of Palaeolithic studies, you will notice that there is marked prevalence of papers dealing with lithic tools, hunting strategies and butchery techniques, over studies on the use of wood, fishing or plant gathering strategies and elements of social life. This disproportion is due to the fact that we are mainly working on material evidence that have survived over millennia. Crafts, arts and leftovers in perishable materials were more numerous than the remnants left for study today. That is how the biggest part of these societies slip out of our science…

Sometimes, unexpected facts emerge, not corresponding to the image we share in our collective consciousness and suddenly give another face to prehistoric hunter-gatherers, such as the women and men who took care of the elder, even the ones having strong disabilities at La Chapelle-aux-Saints, France, the people who wore head-dresses made from red deer stag skulls, maybe for ritual acts at Star Carr, United-Kingdom or the families who put flowers in the burials of their beloved (at Shanidar IV, Iraq and at El Mirón Cave, Spain).

I found myself such an ‘unexpected fact’ in one of the most common motives of prehistoric art: stencil hands. It may be the most unexpected place to find an unexpected fact. Indeed, stencil hands are a kind of universal pattern, an invariant of prehistoric societies. The idea of stencilling one’s own hands even seems to be something pre-programmed in the human brain.

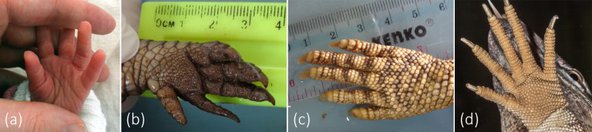

A short time after the discovery of the Wadi Sûra II shelter in Egypt in 2002, one of the biggest rock art site in Africa, there has been a collective emotion around the ‘hands of children’ stencilled on the walls, especially the pair of ‘children hands’ in a pair of adult hands. But when I first came on the site in 2006, I was shocked by the shape, the size and the proportions of those presumed human tiny hands. I immediately thought: How could they be from human children with such pointed fingers, such small dimensions, and such a short palm (less than half of the finger length)?

It would have been a crazy idea to go against all, as I was still a student. I first put the idea in the back of my mind. And year after year, it began to haunt me… It made me sweat each time I suddenly woke up in the middle of the night with the image of a prehistoric hunter-gatherer, being supposedly living before domestication, having a monkey on the right shoulder and stencilling its hands. No, definitely, it was a crazy idea.

Yet, this idea became a hypothesis to be tested. After a preliminary study on a small sample of babies in 2013, I set up an interdisciplinary team and we did a comparative morphometric study on hands with samples of babies born at term and pre-term in the neonatal unit of a University Hospital in France (CHRU Lille). The conclusion was that the tiny stencil hands of Wadi Sûra II were matching less than 0.01% with human babies hands on at least four criteria. It was undeniably not human hands. Monkeys hands? To my surprise, the results of a study I conducted on juvenile Cercopithecidae also seemed to exclude, on morphometric criteria, the hypothesis of monkeys hands. We finally found the best match among reptiles, and our results tend to show that those tiny hands were most probably made from desert monitor lizards (Varanus sp.) forefeet.

An unexpected result that definitely doesn’t stick with our popular imagery on prehistoric hunter-gatherers! The challenge now is to decipher the underlying context and motivations. Needless to say that in Prehistory, further surprises await us under the trowel.

Emmanuelle Honoré is Newton International Fellow at the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research at Cambridge. She is currently conducting a two-year project on the perception and representation of Self and the Other in the rock art of North Africa, funded by the British Academy.