How the Barbaro brothers created the perfect Renaissance villa

by Dr Laura Moretti

23 Mar 2018

In the third episode of the BBC Two series, Civilisations, Simon Schama FBA visits the astonishingly beautiful Palladian villa of Daniele Barbaro in the Veneto, with frescoes painted by Paolo Veronese, contemplating the world of the cultivated country gentleman. This building epitomises a phenomenon which developed thanks to the exquisite work of exceptionally talented artists and the extraordinary substances of exceedingly wealthy patrons. But how did this representation of a perfect world take shape, and who were its protagonists?

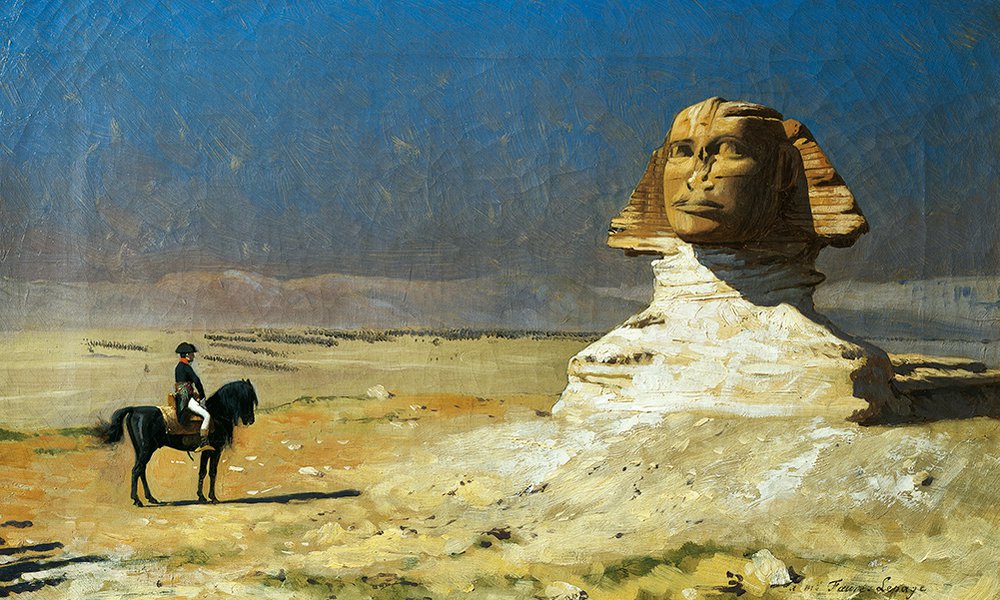

Villa Barbaro, Maser. Designed by Andrea Palladio, c.1554, built 1554-58 (Wikimedia Commons)

A Renaissance trend

Owning a country villa became a trend during the Renaissance, particularly in the Venetian territories. Numerous noblemen, owners of palaces on the Grand Canal, but also of plots of land in the mainland, commissioned new buildings to manage their agricultural businesses and to spend their time during the summer months. They did not just want these properties to be functional, including spaces for agricultural machinery, tools, and animals, but also to reflect and represent their cultural and artistic interests and inclinations. They read Virgil and Pliny, and employed successful artists to shape their aspirations.

Villa Pisani, Bagnolo di Lonigo. Designed by Andrea Palladio, 1542, built 1542-45 (Wikimedia Commons)

Villa Badoer, Fratta Polesine. Designed by Andrea Palladio, 1554, built 1556-63 (Wikimedia Commons)

Commissioned and brought to completion by different individualities, these buildings present common characteristics. Villa Barbaro is one of the most extraordinary examples, expressing the collective effort of extraordinary protagonists.

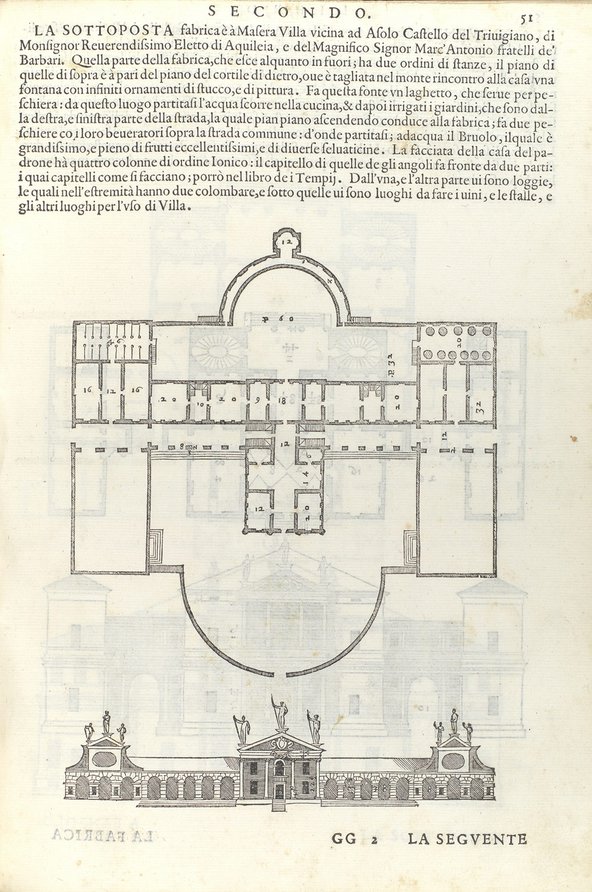

The perfect spot

For a gentleman, it is “highly creditable and convenient” to possess a house in the city, especially if he occupies public posts in the government, but also a house in the country, to control his possessions, to exercise his body walking and riding on horseback, and to recreate his mind reading books and contemplating nature. This model of balanced and happy life is described by Andrea Palladio in the second book of his architectural treatise – I quattro libri dell’architettura [The Four Books on Architecture] – published in Venice in 1570.

The perfect location for the country house is in the middle of the territories, possibly in proximity of a river or a watercourse, on an elevated and agreeable position facing “the temperate region of the air”. The phenomenon of the expansion of patrician land ownership in the territories of the Serenissima became widespread during the Quattrocento. The Barbaro family, which acquired a palace on the Grand Canal in the San Vidal area around the middle of the 15th century, took possession of land in Maser, near Treviso, probably as early as the second half of the Trecento. On the area, there was an earlier building which Palladio took into account when designing the new villa.

Satellite image of Villa Barbaro and its surroundings (Google Maps)

The perfect architect

Andrea di Pietro della Gondola was born in Padua in 1508. Of humble origins, he trained as a stonecutter. When he was sixteen, he moved to Vicenza where he was employed as an assistant to local stonemason. During the 1530s, the Vicentine nobleman Gian Giorgio Trissino (1478-1550) took the young artist under his wing and transformed him into Andrea Palladio – a name which echoed the refined taste and the scholarly mindset of this cultural milieu. The architect was now ready to take commissions from the wealthy nobles who were associated with Trissino. Palladio’s fame quickly spread over the region.

His success was largely due to his ability to match the wealth and social status of the owners with their cultural and artistic aspirations. Palladian villas started to populate the mainland territories of the Republic of Venice, contributing to develop a new attitude towards the landscape. In his treatise, Palladio provides descriptions and idealised drawings of his projects, of which villas constitute a major asset.

Villa Barbaro, from Andrea Palladio, I quattro libri dell'architettura (Venice, 1570). Book 2, p. 51 (New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art).

The perfect painter

Paolo Caliari was born in Verona in 1528 (hence his nickname “Veronese”), where he trained as a painter. He moved to Venice in the early 1550s and stayed there for the rest of his life, becoming one of the leading painters of his time. He received religious and secular commissions in Venice and the Veneto, but also from an international clientele, producing large paintings of biblical feasts, altarpieces, history and mythological paintings, and portraits. His work is characterised by harmonic compositional structure and supreme coloristic effects. In the early 1560s he was employed by the Barbaro brothers to decorate their newly-built villa with themes celebrating the rural, bucolic, cultural, and religious life. The scenes are completed by brilliant illusionistic effects. This is considered one of the most extraordinary cycles of 16th century Venetian frescoes.

Villa Barbaro, Maser. Cruciform Hall, frescoed by Paolo Veronese (Wikimedia Commons)

Villa Barbaro, Maser. Hall of Olympus, frescoed by Paolo Veronese (Wikimedia Commons)

The perfect patrons

The villa that Palladio designed for the Barbaro brothers in the early 1550s became an important model for the definition of a new type of rural buildings and is considered the product of the interaction between the architect and two exceptional patrons. Daniele (1514-70) was a refined intellectual, who spent most part of his life studying and writing, and became Palladio’s mentor after Trissino’s death in 1550. Daniele published a dozen of books on a multitude of subjects and left several unpublished manuscripts. In 1550, he was appointed Patriarch-elect of Aquileia (at that time an important episcopal see in Northeastern Italy) – remaining in post and waiting for the succession, a position he never held. The other brother, Marcantonio (1518-95) was a diplomat who served as the Venetian ambassador to France and to the Ottoman Empire, and subsequently as a member of the Senate influenced the architectural commissions in the Republic for decades. Both created partnerships and personal relationships with the artists they employed. In 1556 Daniele published his translation and commentary on Vitruvius, completed by the marvellous drawings of Palladio, while Marcantonio favoured the architect’s career in Venice. The brothers were portraited by talented artists, including Titian and (unsurprisingly) Paolo Veronese.

Paolo Veronese, Portrait of Daniele Barbaro, 1556-67 (Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum)

The perfect villa

Villa Barbaro sits gently on top of a reclined slope. Elegant and composed, it dominates the landscape. From its windows, you can contemplate the horizon of the flat land. For the owners, an image of their possessions, a measure of their powerful wealth, but also an invitation to meditate on the beauty of the landscape and on the marvels of nature.

Villa Barbaro, Maser. View from the main window of the Cruciform Hall (Wikimedia Commons)

Turning towards the inside, you can appreciate – to echo Simon Schama’s words – “the dreamscapes” created by Veronese, “a perfect slice of Renaissance escapism”. From the back window, you can enjoy the view of the nymphaeum, excavated from the hillside, with his fishpond obtained thanks to an elaborated hydraulic system.

Villa Barbaro, Maser. Nymphaeum (Wikimedia Commons)

More closely related to the grand Roman residences, like Villa Giulia or the villa that Pirro Ligorio built for Cardinal Ippolito d’Este (incidentally the dedicatee of Barbaro’s edition of Vitruvius), than to the Venetian villa-farm, the Villa Barbaro is a masterpiece; the result of the interaction of extraordinary patrons with extraordinary artists. Far from being an abstract ideal, Villa Barbaro is deeply rooted in the historical and cultural context of which it is a marvellous product: a living organism, which is still able to surprise and fascinate.

Dr Laura Moretti is Senior Lecturer in Art History at the University of St Andrews. Her field of expertise is Italian Renaissance art, architecture and music, with a particular interest in the history of early modern books. She is currently the co-director (with Daryl Green) of the impact and research project Thinking 3D.

She has held prestigious post-doctoral positions (Department of History of Art, University of Cambridge, 2005-07; Worcester College, University of Oxford, 2007-10; Villa I Tatti, Florence, 2010 & 2014-15), and in 2014-16 has been the co-ordinator of the International Network Daniele Barbaro (1514-70): In and Beyond the Text, funded by the British Academy and Leverhulme Trust. Among her recent publications are Daniele Barbaro (1514-70): letteratura, scienza e arti nella Venezia del Rinascimento (co-edited, with Susy Marcon, 2015); Daniele Barbaro 1514-1570. Vénitien, patricien, humaniste (co-edited, with Frédérique Lemerle, Vasco Zara and Pierre Caye, 2017).