Are we fighting the right giants?

by Professor Anthony Heath FBA and Dr Lindsay Richards

24 Mar 2015

Just what are the most pressing social issues of today? Last week we launched our new research centre, the Centre for Social Investigation (CSI), with an event at the British Academy. The centre aims to be a source of reliable information on contemporary social issues. But what are the issues that we should be talking about? It’s a surprisingly difficult question to answer.

We started by thinking about the issues identified by William Beveridge in his 1942 report that led to major social reforms in post-war Britain. Beveridge recommended the government fight the five “Giant evils” of Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness. Where are these giants now? We looked at each in turn to evaluate how far we’ve come.

We assessed Want by looking at income and poverty. Our data showed that we have made four decades of more or less continuous improvement; even for those at the 10th percentile (i.e. the position at which 90% of the population receive more) real incomes doubled between 1961 and 2013. And as these numbers might suggest, poverty has declined too. (See Figure 2)

We gauged the fight against Disease by looking at life expectancy; here again we have made considerable progress. People born today are expected to live considerably longer than those born in 1942. What about squalor? We interpreted this as overcrowded housing. Again the data show that strides have been taken to quash this giant although the percentage of overcrowded dwellings may have increased recently, especially in London. Ignorance, assuming it declines with education, is also a giant we’ve been beating back successfully. Idleness is the giant that appears to be alive and well and ever-looming. Unemployment has never returned to the levels seen in the 40s, 50s and 60s.

So, four giants down and one to go? Does this mean they are not the relevant contemporary issues we should be looking at? We’ll come back to this question.

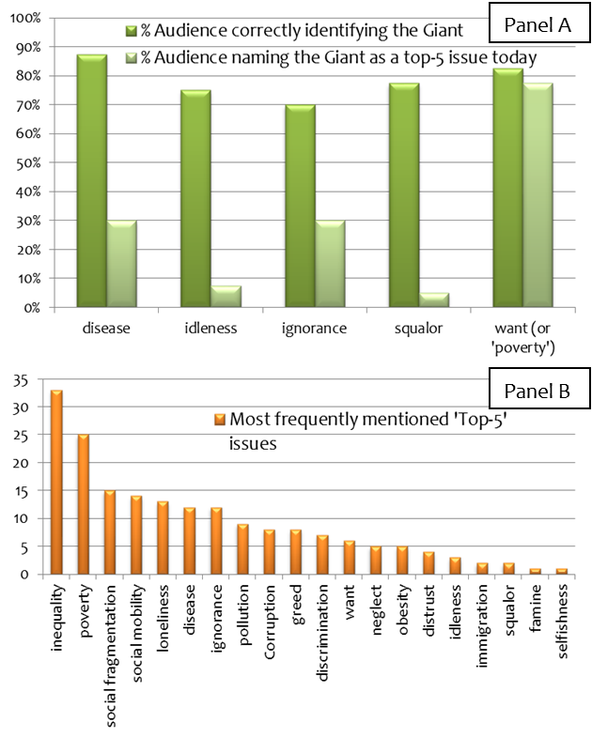

At the CSI launch event, we subjected our audience to a little quiz. We had a room full of people who are engaged in social issues and they, we thought, would be able to help us identify what the big issues are. We asked people to identify Beveridge’s Five Giants. Our (primed!) audience did well – see Fig 1 – and we also asked what issues are the highest priority today. The results were interesting; although almost everyone knew that idleness was one of Beveridge’s giants, less than 10% thought it was still a ‘top-5’ issue today. Yet, unemployment is associated with a high risk of mental health issues, a pattern exacerbated by economic hard times. More than that, this giant is getting meaner about who it picks on, increasingly going for the vulnerable in our society; young people of black, Pakistani or Bangladeshi backgrounds experience far higher rates of unemployment, as do young people of all ethnicities with low qualifications. This giant is not only present but changing its tactics to bully the vulnerable.

And what about the four giants that seem all but vanquished? Despite undeniable progress, there is still cause for concern there too. Poverty and low incomes are much more likely among people of Pakistani and Bangladeshi backgrounds; women are still at the receiving end of a substantial pay gap and may be placed at higher risk of poverty due to the spending cuts. If we include mental health (as we should) in the giant of Disease, progress might be slower than we had assumed. If there had been any improvement in our mental health (as our data hinted at),it was certainly disrupted by the Great Recession.

Figure 1 – Results from our expert audience on Beveridge’s Five Giants and the highest priority issues of today; N = 40 (with thanks to Kerry Mellor and Rachel Dishington)

So who are the new Giants on the block? Many of our audience identified priorities that tap into these themes (Fig 1, panel B). And the most popular answer? More than 80% of our audience picked inequality. And who can blame them? We’re living in an era in which the phrase “the one per cent” is universally understood, in which documentaries and books are dedicated, not just on those at the bottom but the size of the gap between those at the bottom and those at the top.

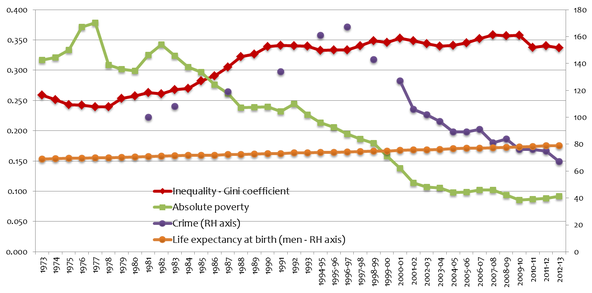

But have we all been wrong about inequality? While there is no question that it is morally reprehensible, where is the empirical evidence of its negative consequences? In Figure 2, we put together some of our findings. The red line shows inequality, and we can see that it increased sharply in the 1980s and continued to rise in the 1990s before slowing and coming down a little after the 2008 recession. However, the trends in crime, life expectancy and absolute poverty have progressed independently of inequality. Life expectancy has been steadily increasing; crime has been coming down since the mid-1990s; absolute poverty has been in long-term decline apart from a ‘blip’ in the late 1970s.

Figure 2 – Absolute poverty, crime and life expectancy have been improving against the current of rising Inequality

In summary then; Beveridge’s giants remain relevant today but more so when we take note of the position of the vulnerable in our society, take account of the changing weapons that some giants may be using, and observe the collaboration between giants. Ignorance, for example, (interpreted as having no qualifications) may increase vulnerability to Idleness, which in turn brings about increased opportunity for Disease (interpreted as the risk of poor mental health) to strike. In this light, we need to be careful that our attention is not distracted by the appearance of new giants on the block.

Briefing notes on the research mentioned in this post are all available online at http://csi.nuff.ox.ac.uk/

Anthony Heath, CBE is a Fellow of the British Academy and the Director of the Centre for Social Investigation at Nuffield College, Oxford. He is Emeritus Professor of Sociology at the University of Oxford and Professor of Sociology at Manchester University.

Lindsay Richards is a postdoctoral researcher at the Centre for Social Investigation at Nuffield College, Oxford.